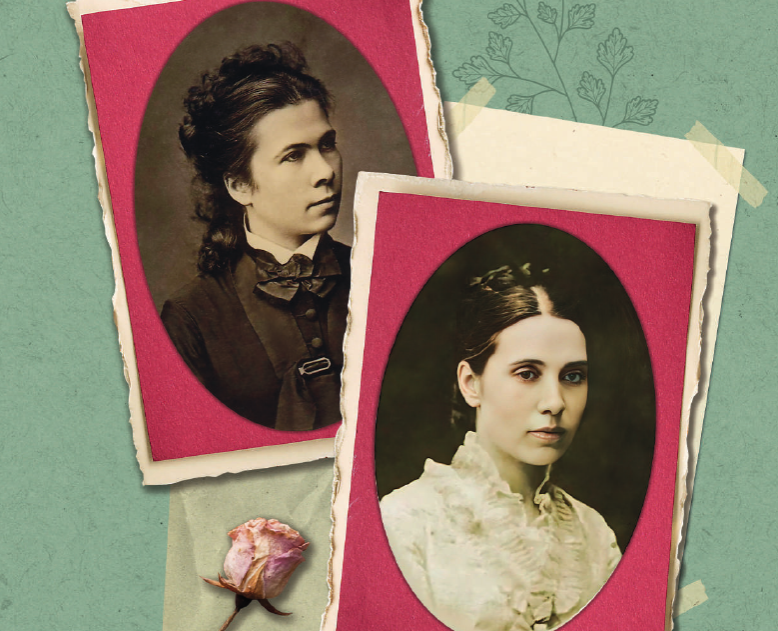

There were its own legends and ghosts in every self-respecting camp — children talked in whispers to each other about them at dark nights. The main pioneer camp “Artek” was no exception. The White Lady occupies a central place in its ghost pantheon. This is a mysterious woman in white emerging near the accommodation units of the camp and bottom of the Ayu-Dag mountain. It is considered that it is the ghost of the famous French adventuress and countess Jeanne de la Motte, who became a prototype for Milady Winter in the novel “The Three Musketeers” by Alexandre Dumas. They say the countess took up residence on the territory of the modern camp “Artek” in Crimea in her later life and her unquiet spirit still wanders here. People say she was buried in those places, but the tomb is forsaken. The legend didn’t come out from nothing, though everything wasn’t quite like that. But first things first.

Ascent of “poor orphan”

Jeanne de Luz de Saint-Remy de Valois came from a family of the illegitimate son of Henry II the king of France. Notwithstanding its dominant name, the family wasn’t rich. “Poor orphan from the House of Valois” — that was how the heroine of this story called herself. When Jeanne was a kid, she asked for alms in the street. Marquise Bulevilier saw her there, took pity and decided to help the girl: she arranged her to come to the finishing school at the monastery. However, Jeanne turned out to be an ungrateful and seemingly not so noble maiden: when she was 22, she ran away from the monastery with her fiance, who was a guards officer and whom she married later and after that she became the countess de la Motte. Using her acting abilities and brains, the newly-minted countess formed essential connections in aristocratic circles — and the best houses of France opened their doors to her.

Jeanne de la Motte went down in history owing to the most sensational fraud of XVIII-th century. Having decided to make a gift to madame du Barry, the king Louis XV commissioned an unbelievable necklace from jewelers — it consisted of 629 diamonds. He did make the order, but he died before he could buy the jewel. His successor Louis XVI rejected to buy the necklace for Marie Antoinette, as it was too expensive. Jeanne could persuade the cardinal Rohan that she was friends with the queen and she was able to rebuild good relations with the royal couple. In 1785, the countess de la Motte made the cardinal sign a contract with the jeweler for buying-out of the necklace — it is said that it was at the wish of the queen. After that, Jeanne took the jewel to pass it to her “friend” Marie Antoinette, — and as you guess it, nobody saw those diamonds. The huge scandal erupted. Regardless of the fact that Marie Antoinette wasn’t involved in the fraud, but her name was stained and the royal authority’s prestige declined, what lead to the French Revolution.

So, what did happen to the adventuress? Jeanne was arrested, taken to the Bastille prison, whipped and branded with fleur-de-lis — the countess was stripped to the waist and the mark in the form of V was made by burning it out upon the skin, what means voleuse (translated as “thief” from the French language — editorial note). However, the disgraced noble woman contrived to break from the jail very soon. After a while, she showed up in London and where she supposed to die in 1791 and she “rose from the dead” under another name few years later, she became countess de Gasche. Afterwards, she left Europe and settled in Saint Petersburg in Russia. She represented herself as a victim of the French Revolution. With time, her outrageous past was revealed and the emperor Alexander I determined Crimea as a place of residence for the countess — it was a far and wild region back then.

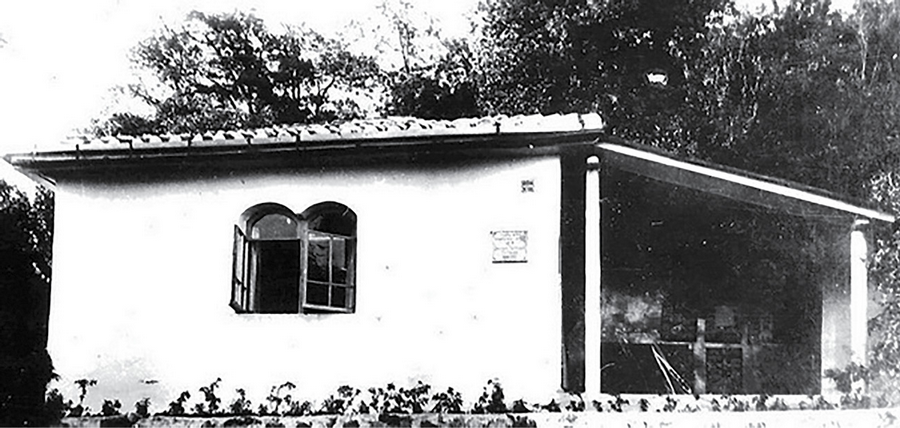

Damn house built of rubble stone

The oldest building located on the territory of the “Artek” camp is so-called the House of Zinoviev: it’s a small facility, where the founder of the pioneer camp Zinoviy Soloviev lived in during the period of 1925-1928. Anyway, very often the building is called in the different way — the Damn House. The story of this evil moniker goes back to our French heroine. The countess de Gasche — let’s call her like that — arrived in Crimea with the group of missionaries headed by the princess Golitsyna and baroness von Krudener in August 1824. The princess and baroness were going to establish a colony within Crimea recently gained by Russia and preach the Christianity here. The countess de Gasche had little interest in the religion, but let’s not forget that she visited the peninsula against her own free will and joined her fellow travelers not in her desire.

It’s considered that firstly Jeanne (she kept the previous name) stayed at the estate of the princess Golitsyna in Koreiz and then she lived in Gurzuf during a short period of time, at that Damn House, which was almost the only dwelling on the whole line from Gurzuf to the Ayu-Dag mountain. It must be said the house was (and it is preserved to this day) very small: 5,8 meters long, 3,75 meters wide and 4,5 meters high (this is an exterior height of the roof, but not an interior height of the ceilings). The house is built of rubble stone with lime mortar — the builder of that facility and its first owner was a local master on lime burning-out. As a legend states (oh yeah, a new legend again — the countess was literally wrapped in mysteries) that not good affairs were handled in the Damn House: Jeanne de Gasche allegedly got all the smuggling under her control within this area, made a path from the coast through Ayu-Dag, the lights were always on in her lodgment at nights and strange people came to her. This smuggling fuss bears little resemblance to the truth, but the fact that Jeanne de Gasche live in Gurzuf for some time (it’s more likely it was the brief period of time) is quite possible. Nevertheless, she didn’t plan to stay here until the end of her days — very soon, she moved to Staryi Krym.

Old woman of the average height

Such a choice may seem strange — why should a person move from one remote place where the sea was to another one? The point is that the countess missed the upper class society (frankly speaking, she was indifferent to the beautiful landscapes of the peninsula) — and her relocation to Staryi Krym is caused by the wish to get closer to the family of the baron Alexander Bode. He was an educated and rich man, son of the French emigrant, possessed the estates in Sudak and Staryi Krym. He was characterized by the rare hospitality spread to the out of favor countess. The daughter of Alexander Bode called Maria left interesting memories about the new friend of the family.

“I knew her wonderful story much later; I don’t know why she impressed me then; but now I see an old woman of the average height, who was pretty neat and wearing a grey woolen redingote. Her silver hair was covered with a velvet beret decorated with feathers; I can’t say she’s got a meek face, but it looks like pleasant and smart with the bright and shining eyes on it. She was speaking French glibly and fascinatingly. Many people whispered about her oddities and hinted there was something mysterious in her fate. She knew about that and kept silence without denying or confirming the conjectures; sometimes she even liked to instigate such conjectures seemingly via an intentional slip of tongue with educated people and as for shallow and ordinary locals, she confused them with mysterious allusions. She was talking about the count Cagliostro and different persons of the Royal Court of Louis XVI, as it seemed they were people around her. So her conversations were passed from mouth to mouth during a long period of time and became subjects for guessing and interpretations. She wanted to buy my father’s garden located in Staryi Krym. It was a decent housing for such a mysterious lady. Crimean khans were the owners of that estate once and there were the ruins of the mint and dungeon, the front part of which served as a root cellar in our household and the rest part of the dungeon is swamped with big stones. The folk tale stated that a Khan’s moor guarded treasures there”, — Maria Alexandrovna described her impressions from the acquaintance with the countess de Gasche. When she met Jeanne, the countess was 68 years old.

Guitar as a gift

However, the purchase of the estate located in Staryi Krym did not take place — Jeanne bargained with Bode endlessly and thereat, she drove potential buyers off the estate, what broke her relations with the baron. Then, when the countess became seriously ill, she apologized to the baron and presented some things to him as a token of friendship. “These things were: beautiful gown for my mother, Italian guitar for me and perfect books for my father. Not knowing how to understand that weird deed and fearing to offend the countess with his refusal, my father sent a case of best wines to her, whose price equals to her gifts, for restoring her vitality and health and asked her to take her gifts back after her full recovery. She got well, but she didn’t want to hear anything about taking the things back, so we remained on friendly terms. When my father arrived in Feodosiya, he always visited the comtesse, talked to her a great deal of time and he was always charmed by her conversations full of observancy, world knowing and some mystique”, — Maria Bode wrote about. Shortly afterwards, the comtesse de Gasche decided to settle in Sudak — she liked Staryi Krym even less than Gurzuf.

The baron Bode enthusiastically welcomed that proposal — the countess promised him to work on his daughter’s education and help his wife with the household work, as well as tell him a lot of useful. He started building the house for Jeanne in Sudak in the fall of 1825 on a gratis basis. The construction operations were supposed to end by the spring of 1826, but a courier from Staryi Krym came to the baron to tell the news that the comtesse got sick and wished to see him. He immediately went to Staryi Krym, but it was too late — the countess had died.

Two spots on the back

An old Armenian woman, who served her, said that when the countess felt bad, she spent the night going through the papers and throwing them into the fire; she prohibited to touch her body and told to bury her in the cloth she dressed; she said that her body would be called for and taken away and there would be many disputes and discords around her burial. Although, those predictions were not fulfilled: due to the lack of catholic priest, the countess was buried by Russian Orthodox and Armenian Arian priests. The gravestone has never been touched to this day. That Armenian woman couldn’t satisfy the common curiosity: the servant was allowed to help the comtesse very seldom, Jeanne got dressed without assistance and entrusted her servant only the menial work in the kitchen; only washing the dead body of the countess, the Armenian woman noticed two spots on her back, which are supposed to be branded with iron. Soon after the government in Saint Petersburg heard the rumors about the death of the countess, then the courier from the count Benckendorf came with the requirement to get the comtesse’s locked small chest, which was immediately transferred to Saint Petersburg and that time the governor told my father he was entrusted with the task to watch the woman and it was the fact she was the countess la Motte-Valois taken refuge in Russia.

The comtesse’s chest, more well-known as a dark-blue jewelry box among researchers of that story, was empty — there were no the papers “which merit the attention of the government” inside of it. A small house in Staryi Krym, where Jeanne de la Motte aka Jeanne de Gasche lived in, went through in the Russian Revolution of 1917, but it wasn’t preserved to this day. The Armenian cemetery she was buried in and her grave weren’t preserved either. The photo of the gravestone only exists. There was no any date on that gravestone — the plate of the lower part of the gravestone remained intact. The vase with carved leaves and small cross are depicted in the upper part of the stone. The photo of the gravestone is kept in the Literature and Art Museum in Staryi Krym — that was all left of the great French adventuress.

Reference: Crimean Magazine