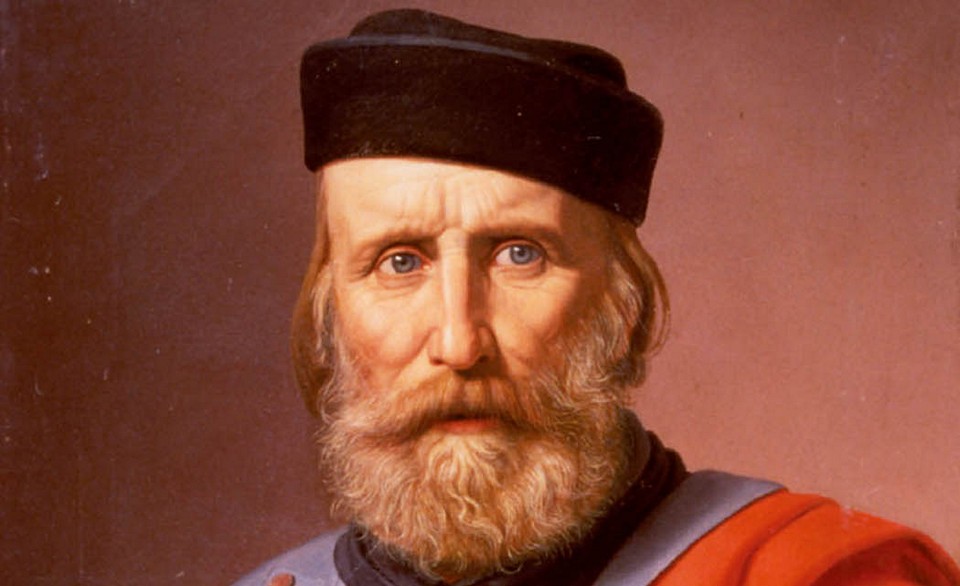

Giuseppe Garibaldi was standing on a bow of a schooner tilting on the waves and wistfully looking far at the unknown shore appearing at the horizon. The sails were rippling in the wind and waves of the Black Sea were rolling on a board. A coasting-vessel loaded with olive oil bottles and Italian textiles has been moving to Kerch along the local shores for several days and Giuseppe could see Crimean landscapes, which looked like the expanses of his Motherland so much…

That could be a nice introduction of a book describing a national Italian hero’s visit to Crimea and the importance rate of the role he played both in the fate of Italy and Russia during his presence on the territory of the Crimean peninsula. However, our region’s guests a Russian man Nikita Hohlov and Italian woman Stefania Zini (she’s been living in Russia for twenty years) are scientists, but not fiction writers. Therefore, though their scientific reports dedicated to the ethnogenesis of Italians in Crimea and along with that these researching works are written only in an official style. The employees of the Commission on Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Geographical Society Nikita and Stefania have come to the Republic of Crimea many times before to investigate origins of Italian colonists’ Crimean descendants. Besides of it, the researchers want to find out why Italian colonists decided to settle down in Crimea and what kind of features modern Crimean Italians, whose great grandfathers and great grandmothers spoke the Italian language, got from Apulians, Tuscans and Ligurians.

True Italians

In the first third of the XIX -th century, Crimea became a home for several dozens of Italian families, who had accepted the citizenship of the Russian Empire and decided to stay and live in the region. They were mainly sailors involved in coastwise shipping operations. It was rather obvious that they were interested in Russian Crimea. They just wanted to find new opportunities, get a better life and release their trade mission. So, we want to mention that according to the law of that time period, all the sea ports were available for a coastwise navigation. Moreover, those Italians, who moved to the South of the Russian Empire in Tauris and took out the Russian citizenship, could buy, sell and take on lease land properties without any restrictions. As for foreigners, they were prohibited to perform such actions. The export goods the Merchant Fleet carried out were rye and avena plants, brans, oil cakes, ore and wood. The products imported by the Fleet were alcoholic beverages and fabrics.

Italian families in Crimea usually settled down in districts of Kerch and Feodosiya. They built houses, Catholic temples, brought new varieties of tomatoes to Taurida and of course, they took their perfect Mediterranean tan skin, passion for Italian pasta and especially their melodic language.

Stefania Zini and Nikita Hohlov look for evidences of Italian colonists’ stay in Crimea both in archives (besides the Crimean ones) and among grave stones with erased writings on them standing in Crimean cemeteries. Our Crimean guests research DNA components of Italian families’ descendants too. There are about three hundred of Italian descendants live on the territory of Crimea. Stefania and Nikita could take jaw imprints, saliva and buccal epithelium samples from Italians in Crimea in their last ethnographic expedition. All the samples were delivered to the Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography in Moscow for further exploring activities. The investigation procedure is very expensive, but it’s very interesting cause it can shed some light on the mystery of the Crimean Italians’ origins. We will be able to know whether they came from the Southern part of the Apennines or from the Northern one.

Our scientific guests tell they are going to get the same anthropological samples from full-blooded Italians living in those provinces, where ancestors of Crimean Italians came from. By the way, scientists will have to accomplish a time-consuming but exciting job. In the other words, they will research papers in different Italian archives and even in the famous and almost inaccessible Vatican Apostolic Archive, which keeps a lot of secrets within its building.

Garibaldi’s Crimea

Nikita Hohlov wants to find an answer to an issue of global concern right in archives of Vatican. That issue is connected with a role of Russian Crimea in the destiny of the Italian national hero Giuseppe Garibaldi.

From the age of fifteen, Garibaldi served as a sailor on merchant vessels entering ports of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. In April 1833, he was a captain of the schooner “Clorinda” and he decided to put into the port of Taganrog. Here, young Giuseppe joined the secret political movement “Young Italy”, whose aim was liberation of his Motherland from the Austrian domination and creation a united Italian republic. Within the walls of that movement, Garibaldi swore an oath to give his life for the freedom of Italy. The “Clorinda” boat could never pass over Kerch. Some time ago, a consulate of the Kingdom of Sardinia existed in Kerch. The uncle of our Italian hero Antonio Garibaldi headed the consulate. He died in 1846 and buried with honors in the city cemetery.

In one of repositories, Stefania and Nikita found a document signed by a Russian citizen Giuseppe Garibaldi. On the other hand, was that person Garibaldi the world knows or was it just a same name guy?

Along with that, we are reliable informed the Italian freedom fighter’s relatives were scattered on the territory between Berdyansk, Feodosiya, Taganrog, Kerch and Odessa. Thanks to our guests, we are able to know that some of Garibaldi’s relatives left Italy because of political reasons. Giuseppe’s cousins lived in Crimea too. In 1849, which was the year of the Italian revolution’s defeat, he visited them very often and stayed long in their apartments.

Many questions appear in people’s heads. Which way did Crimean Masonic lodges mostly concentrated in Feodosiya influenced on the Garibaldi’s philosophy of life? Who actually was a revolutionary teacher of Giuseppe? Was he a citizen of the Russian Empire? Did Russians fund the revolution in Italy? Currently, that’s supposed to be just simple questions. A true investigators’ task is to find the proper answers.

Nikita and Stefania think that if it turns out the Italian revolutionist was a Russian citizen according to his passport, so it will be a real scientific sensation then. Nikita is quite sure the Garibaldi’s Crimean long stay is his lodgment required for next actions. Having visited Crimea, Giuseppe found comrades-in-arms, like-minded fellows and the way to arrive into a new shelter in the USA. For example, old steam-vessels’ logs kept records about a bought ticket in Giuseppe Garibaldi’s name. It’s written there that a ship was moving from Russia to far lands of the New World. Later, Garibaldi will meet a Russian revolutionist Alexander Herzen. After, being a guest, Garibaldi gave a toast in the flat of Alexander Ivanovich for liberation of Russia from the emperor’s rule.

As an experienced craftsman strings beads on a thread, the same way Stefania and Nikita collect facts about Garibaldi in Russia. Here, we can know about his acquaintance with Nikolai Pirogov and Dmitri Mendeleev. On top of all, in investigation reports you can find the truthful information about activities of Italian architects, who raised palaces on the Southern Coast of Crimea and placed Masonic symbols in building furnishings. Furthermore, not so many people know that the well-known Garibaldi’s Thousand consisted of Russian people up to 30 percent of the whole military staff…

While, all these beads are spread across and an investigator’s task is to line them up.

One thing that is very interesting, first Italian families arrived in Crimea are changed by other ones. Before the October Revolution, as a plenty of emigrants went back to Italy, so new free places were occupied by other Italian families, which became parts of a skeleton staff of the well-known kolkhoz named after two Italian workers Sacco and Vanzetti.

In 1929, Italians with Italian passports on the territory of Crimea numbered in 800 people and several times more by the Italian blood. Crimean Italians maintained both the national community and primary school at their own expenses. A number of Italian immigrants in Crimea were increasing due to incoming Italian communists and antifascists.

On the bottom

With the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, immigration flows were ceased. In January-February 1942, all the Italian population of the region was totally deported from Kerch in the interests of the national security. Primarily, it was planned to deport Italians right after Germans in 1941. Nevertheless, those intentions were not fulfilled, as Kerch was occupied by Wehrmacht troops in November 1941. In 1942, the city was liberated the first time and deportations of the Italian population were continued implementing. In the end of January and beginning of February 1942, Italian families were transported to the Caucasus by sea boats and after they were carried away to Central Asia. The first sea-going barge departed off the coast sank not far from the Kerch’s harbor in front of local citizens’ eyes. The iced water and strong current didn’t give any chances people to save their lives. Nobody of them survived. Probably, died people took back to their graves the response to a question why natives of the Apennines liked Crimea so much and why Russia welcomed sailors of the Italian Merchants Fleet so cordially.